2.4 NAME: CARLOS

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: VENEZUELA

AGE: 28

CHILDREN: 2 KIDS

ORIGINAL OCCUPATION: CAR MECHANIC

TIME ON THE ISLAND: 2 YEARS

I have risked my life 3 times to come here. This is the third time I’m on the island. It’s not a trip I would recommend anyone to take. We’re put in just a wooden little boat, always overloaded with too many passengers. I’m not from the coast, so I was nervous the first time. I’m from the city. I’m not used to be out on the sea. I keep throwing up the whole trip.

I’m from Barquisimeto and travelled 6 hours to get to Falcón, from where the boats leave. But when you get there it takes some time, sometimes months, to wait for a boat to leave. Sometimes the sea is too rough, sometimes the engines stop working or they have to fix the boat. They put you up in a house somewhere far. With no food and you can’t work because you have to be ready if they’re ready to do another crossing. It can happen that they get caught and are arrested too, because it’s human trafficking that they’re doing. It’s illegal in Venezuela as well. It’s a risk for us too, to stay in such a house. If the authorities find us there, we get arrested.

The crossing takes 9 hours, sometimes more. Where Venezuelan waters come together with Curaçao waters, the sea is different. They call it The Channel. That’s when they have to lower speed, which makes the journey even longer. When they finally get close to the island, they’ll throw you out anywhere they can. Their mission is to get you here, but they don’t care how you make it to land.

Some people come by yacht, not the wooden boats we came in. The trip by yacht is more expensive, but it’s safer. Those people sometimes bring their families and children. But it’s always a risk. Remember there have been 2 accidents. One was recently, when a boat of 38 people disappeared and was never found. They only found 1 person, with two bullets in the chest.

In 2017 I had finished working and was in the bus going home. The police stopped the bus and asked for everyone’s sedula. They arrested me and took me to the barracks. [The barracks are make-shift accomodations for the undocumented. They’re located on the prison grounds; Red.] It’s not good in there. When the guards are in a bad mood, they mistreated us or sometimes skip someone when giving out food. And you just have to wait until your family can buy you a ticket to Venezuela. If they can’t, you’re stuck in those barracks and left to rot in there. 20-30 men in 1 room. No ventilator. Mosquitoes. Just a few mattresses on the floor. It’s inhuman. When you finally get out you feel like never ever coming back. Back then I was lucky and after only 1 week my wife bought me a ticket to Venezuela.

Once back in Venezuela you realize that it’s still bad there too. One of the biggest petroleum countries in the world, now in a petroleum crisis. Some states in Venezuela have it better than others, but it’s still difficult. There’s food but very expensive. Making only $2 a month, you really can’t do anything else but buy food. No social life possible. Back in Venezuela my mom takes care of my two children. My wife and I are here trying to earn enough to send some back home. I want my kids to eat well. Not just the legumes that the government gives them. I want them to have meat and vegetables, salads. When I was working, I would send money every time I got paid. I was working in construction before the corona crisis, but there’s not much construction happening at the moment. I haven’t been able to send them any money so they’re eating only the legumes that come in the government boxes.

When I first came here my life got better, but when covid-19 came to the island it went back to bad. I’m lucky that I got the ‘karchi’ card from the Red Cross. At first, I was worried to register for the card, but we’ve been living with what I’ve gotten through the card. It has helped us out these past months. I’m very, very thankful for the money that came from The Netherlands and for the Red Cross for doing the distribution. It felt like taking a risk, to register, but it has been a great benefit. I get ANG 150,- per month for us as a couple. Since the crisis I’ve only had work a few days here and there, sometimes a week, but nothing regular. Our landlord kicked us out in the middle of the lockdown, because we couldn’t pay rent. We can’t just go and get any job that’s available. They won’t take us. We always have to keep a low profile. Move around without attracting any attention.

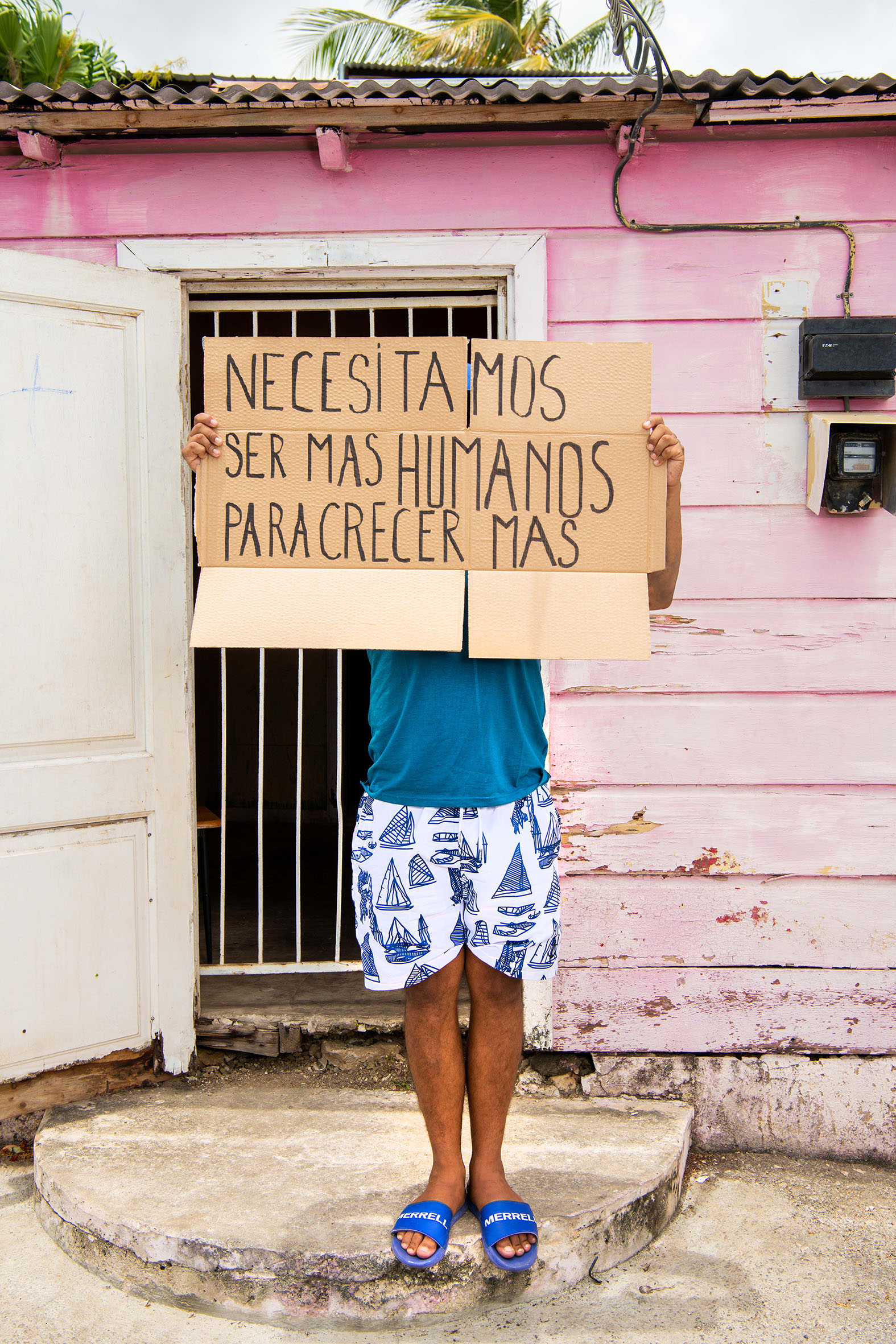

My dream is that people become nicer to each other like before the corruption. No one helps another out anymore. Even just getting a pill for a headache from someone will cost you. I’m working towards my goal of opening a toko back in Barquisimeto, like my parents did, and just live a normal life. To me, this crisis in Venezuela is like a learning curve. We Venezuelans were too lazy and spoiled before. The ones who don’t learn during this crisis are never gonna learn.

The crossing is horrible, but horrible to hopefully become successful. Because if you don’t shoot, you’ll always miss. If we stay there, we die from hunger or something else. We come here looking for a future. Sometimes it works out and sometimes it all comes to a halt, but we have to keep moving forward.

My thanks go out to all the people who helped with this project:

Project Creator & Manager: Berber van Beek ( Studiorootz – photography)

Photography: Berber van Beek

Text and Interview: Yolanda Wiel & Berber van Beek

Translator’s: Carlos Monasterios en Judy Wassenberg

Assistant: Ivonne Zegveld, Mareine van Beek en Reina Keijzers

Spanish translation:

2.4. NOMBRE: CARLOS PAIS DE ORIGEN: VENEZUELA EDAD: 28 NIÑOS: 2 NIÑOS OCUPACIÓN ORIGINAL: MECÁNICO DEL COCHE

TIEMPO EN LA ISLA: 2 AÑOS

He arriesgado mi vida 3 veces para venir aquí. Esta es la tercera vez que estoy en la isla. No es un viaje que recomendaría a nadie. Nos ponen en un pequeño bote de madera, siempre sobrecargados con demasiados pasajeros. No soy de la costa, así que estaba nervioso la primera vez. Yo soy de la ciudad. No estoy acostumbrado a estar en el mar. Estuve vomitando todo el viaje.

Soy de Barquisimeto y viajé 6 horas para llegar a Falcón, de donde salen los barcos. Pero cuando llegas allí, lleva algún tiempo, a veces meses, esperar a que parta un barco. A veces el mar está demasiado revuelto, a veces los motores dejan de funcionar o tienen que arreglar el barco. Te alojan en una casa en algún lugar lejano. Sin comida y no puedes trabajar porque tienes que estar listo para cuando ellos estén listos para hacer otro cruce. Puede suceder que los atrapen y también los arresten, porque lo que están haciendo es trata de personas. También es ilegal en Venezuela. También es un riesgo para nosotros quedarnos en una casa así. Si las autoridades nos encuentran allí, nos arrestan.

La travesía tarda 9 horas, a veces más. Donde las aguas venezolanas se unen con las aguas de Curazao, el mar es diferente. Lo llaman El Canal. Ahí es cuando tienen que reducir la velocidad, lo que hace que el viaje sea aún más largo. Cuando finalmente se está cerca a la isla, te echan donde puedan. Su misión es traerte aquí, pero no les importa cómo llegues a tierra.

Algunas personas vienen en yate, no en los botes de madera en los que entramos. El viaje en yate es más caro, pero es más seguro. Esas personas a veces traen a sus familias e hijos. Pero siempre es un riesgo. Recuerde que ha habido 2 accidentes. Uno fue recientemente, cuando un barco de 38 personas desapareció y nunca fue encontrado. Solo encontraron a 1 persona, con dos balas en el pecho.

En 2017 había terminado de trabajar y estaba en el autobús de regreso a casa. La policía detuvo el autobús y pidió la cedula de todos. Me detuvieron y me llevaron al cuartel. [Los barracones son alojamientos provisionales para los indocumentados. Están ubicados en los terrenos de la prisión; Rojo.] No es bueno ahí. Cuando los guardias estban de mal humor, nos maltrataban o, en ocasiones, se saltaban a alguien al repartir la comida. Y solo tienes que esperar hasta que tu familia pueda comprarte un boleto a Venezuela. Si no pueden, estás atrapado en esos barracones y te dejan pudriéndote allí. 20-30 hombres en 1 habitación. Sin ventilador. Mosquitos. Solo unos colchones en el suelo. Es inhumano. Cuando finalmente sales, sientes que nunca más volverás. En ese entonces tuve suerte y después de solo 1 semana mi esposa me compró un boleto para Venezuela.

Una vez de regreso en Venezuela, te das cuenta de que allá también está todo mal. Uno de los países petroleros más grandes del mundo, ahora en crisis petrolera. Algunos estados de Venezuela lo tienen mejor que otros, pero sigue siendo difícil. Hay comida pero muy cara. Con solo $ 2 al mes, realmente no puede hacer otra cosa que comprar comida. No es posible la vida social. En Venezuela, mi mamá cuida a mis dos hijos. Mi esposa y yo estamos aquí tratando de ganar lo suficiente para enviar algo de regreso a casa. Quiero que mis hijos coman bien. No solo las legumbres que les da el gobierno. Quiero que coman carne y verduras, ensaladas. Cuando estaba trabajando, enviaba dinero cada vez que me pagaban. Estaba trabajando en la construcción antes de la crisis del corona, pero no hay muchas obras en este momento. No he podido enviarles dinero, así que solo están comiendo las legumbres que vienen en las cajas del gobierno.

Cuando llegué aquí por primera vez, mi vida mejoró, pero cuando el covid-19 llegó a la isla volvió a empeorar. Tengo suerte de haber recibido la tarjeta “karchi” de la Cruz Roja. Al principio, estaba preocupado por registrarme para la tarjeta, pero hemos estado viviendo con lo que obtuve a través de la tarjeta. Nos ha ayudado estos últimos meses. Estoy muy, muy agradecido por el dinero que vino de Holanda y por la Cruz Roja por hacer la distribución. Sentí que tomaba un riesgo, registrarse, pero ha sido un gran beneficio. Recibo ANG 150, – por mes para nosotros como pareja. Desde la crisis solo he trabajado unos días aquí y allá, a veces una semana, pero nada regular. Nuestro casero nos echó en medio del cierre porque no podíamos pagar el alquiler. No podemos simplemente ir a buscar cualquier trabajo que esté disponible. No nos aceptarán. Siempre tenemos que mantener un perfil bajo. Hay que moverse sin llamar la atención.

Mi sueño es que las personas se vuelvan más amables entre sí como antes de la corrupción. Ya nadie ayuda a otro. Incluso conseguirle una pastilla para el dolor de cabeza de alguien le costará. Estoy trabajando para lograr mi objetivo de abrir una bodega en Barquisimeto, como hicieron mis padres, y simplemente vivir una vida normal. Para mí, esta crisis en Venezuela es como una curva de aprendizaje. Los venezolanos éramos demasiado vagos y mimados antes. Los que no aprenden durante esta crisis, nunca aprenderán.

El cruce es horrible, pero horrible para, con suerte, tener éxito. Porque si no disparas, siempre fallarás. Si nos quedamos allí, morimos de hambre o de otra cosa. Venimos aquí buscando un futuro. A veces funciona y, a veces, todo se detiene, pero tenemos que seguir avanzando.

Mi agradecimiento a todas las personas que ayudaron con este proyecto:

Creadora y directora del proyecto: Berber van Beek (Studiorootz – Photography)

Fotografía: Berber van Beek

Texto y entrevista: Yolanda Wiel y Berber van Beek

Traductores: Carlos Monasterios en Judy Wassenberg

Asistentes: Ivonne Zegveld, Mareine van Beek en Reina Keijzers